England’s Evangelistic Slaveholder, George Whitefield (1714-1770), above left, was a young, white itinerant evangelist who became the first international celebrity by ushering in the First Great Awakening, with the beliefs that one could question authority and experience an open, personal relationship with God.

Jonathan Edwards’s wife, Sarah, remarked, “He makes less of the doctrines than our American preachers generally do and aims more at affecting the heart. He is a born orator. A prejudiced person, I know, might say that this is all theatrical artifice and display, but not so will anyone think who has seen and known him.”

Few churches could hold Whitefield. He is said to have preached 18,000 sermons, often to outdoor throngs of 20,000 and more. Benjamin Franklin publish some of them. He crossed the Atlantic thirteen times. In 1738, he visited Savannah, GA, and returned in 1739 with funds to start an orphanage and school named Bethesda that became his lifelong mission. While there in 1740 he published, An Open Letter to the Planters of South Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland, chastising them: “I think God has a Quarrel with you for your Abuse of and Cruelty to the poor Negroes.”

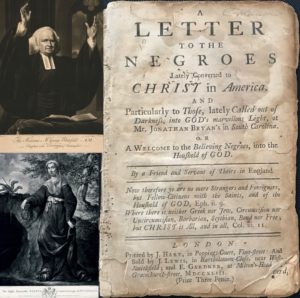

Whitefield soon found a kindred spirit in benevolent slaveholder Jonathan Bryan. Following his example to care for, evangelize, and teach his slaves, Whitefield began inviting the enslaved to participate in his spiritual revivals. Above right, the reverend publishes A Letter to the Negroes, from England in 1743, this time to the slaves themselves, “Particularly to Those at Mr. Jonathan Bryan’s in South Carolina,” cited in the pamphlet’s onerous title. Note that scriptural references on its cover warn that master and bond servant are equal before God.

Bryan then moved his family to Georgia, in time, establishing three plantations outside Savannah, including Brewton Hill, the largest rice plantation in America. Bryan cared deeply for his chattels, even providing a barn for preaching and teaching, and having his favorite slave, Andrew (1716-1812), ordained a Baptist minister in 1788. Bryan wrote, “What concerns me more than all, is the unhappy condition of our negroes. The clothes we wear, the food we eat, and all the superficialities we possess, are the produce of their labors, and what do they receive in return? Nothing equivalent.”

Despite calling himself “a Friend and Servant of Theirs” on the pamphlet’s cover, Whitefield himself was no abolitionist, and believed slavery was essential in spreading European civilization – all the while proclaiming that black children were intellectually equivalent to white. Although he never visited Africa, he thought slaves would be better off in America if only treated humanely, and proposed having them return to evangelize their African brethren.

By 1747, Whitefield attributed the persistent financial woes of his beloved orphanage to Georgia’s 1735 prohibition of slavery. Thereafter, between 1748 and 1750 he vigorously maintained the young colony could never become prosperous until slavery was legalized, which came to pass the following year. It may have been Whitefield’s energetic and conspicuous advocacy for slavery that became the norm for churchmen of the South. To that end, he cited providential and scriptural justifications, and leveraged his income to buy more slaves. Bethesda continues to this day as Bethesda Academy.

Selina Hastings (lower left). A British dowager, the Countess of Huntingdon (1707-1791), was a prominent religious leader and philanthropist who supported and administered Bethesda from afar, as well as making the reverend her personal chaplain. When Whitefield died in 1770, he left everything in Georgia to the countess, including 4,000 acres and fifty slaves.

Another devotee was the teenage slave-poet Phillis Wheatley, who adored Whitefield as an occasional guest to the Boston home of her mistress, Susanna Wheatley. Phillis wrote an elegy “On the Death of the Rev. Mr. George Whitefield,” offered for sale as a broadside just eleven days after his sudden death in Newburyport, Massachusetts. Calling him a “happy Saint” in its opening line, her second stanza begins:

Behold the prophet in his tow’ring flight!

He leaves the earth for heav’n’s unmeasur’d height,

And worlds unknown receive him from our sight.

There Whitefield wings with rapid course his way,

And sails to Zion through vast seas of day.

This became the 17-year-old’s most famous poem, and Phillis would soon agree to visit England’s wealthy Selina Hastings, clearly addressed as the “Great Countess,” in the poem’s second to last stanza, who would patronize the 1773 publication of Wheatley’s groundbreaking volume, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral.