African American Soldiers Incarcerated, and The Civil War’s Great Escape.

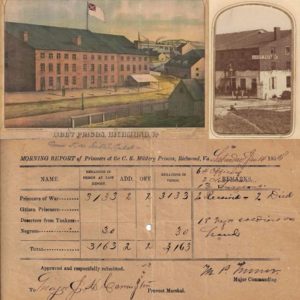

Above, an exceedingly rare document titled, “Morning Report of Prisoners at the C.S. Military Prisons, Richmond, Va,” has a receipt spike hole in the center and is signed by the warden, Major Thomas P. Turner, on Saturday, January 14, 1865. The prisoner tally from the infamous Libby Prison shows a total of 3,133 Union POWs held along with 30 Negroes. Included in the latter figure, a bold notation cites, “18 Negro soldiers on hand,” as well as “13 surgeons, 2 Chaplains, and 64 Officers.”

As black troops of the XXV Corps approached Richmond on April 3, 1865, the city was a mass of flames. But the 36th USCT leading it was ordered to halt below city limits, and cheered a passing white regiment, the 40th Massachusetts Infantry (3rd Brigade, 3rd Division, XXIV Corps), which though still hotly debated, entered first. Next, the 4th Massachusetts Calvary rushed in to free those confined within Libby’s walls, but found its doors wide open. First Lt. “J. [James] A. Litchfield” (written in pencil), of the 40th Mass. Infantry, subsequently entered and kept the Morning Report as a souvenir, or perhaps in remembrance of the prisoners’ ordeals.

Top left, a northern print of Libby Prison as sketched by former prisoner, W.C. Schwartzburg, Co. A, 24th Wisconsin Vols., in mid-1864 (Library of Congress).

Richmond had seven military prisons with several near Cary Street’s Tobacco Row on the James River waterfront. As war began, the firm Luther Libby and Son was given just 48 hours to vacate their three-building ship’s supply, grocers, and tobacco warehouse complex to house captured federal officers.

By May 1863, the Confederate Congress angrily responded to the Emancipation Proclamation’s enlistment of blacks by refusing to trade black prisoners and any white officers who led them into battle. Lincoln insisted that all prisoners be treated equitably and suspended prisoner exchanges until the South complied. Prison populations on both sides multiplied, and Libby’s 4,000 men now slept on cold, hard floors, packed on their sides like sardines to conserve heat and space. A leader for each group periodically ordered them to roll over in unison.

Worse, they were not allowed outside for fresh air and exercise, and rations were limited to rock-hard corn bread, rancid meat, and bug-infested soup. Upon their release from Libby in early 1863, exchanged Union surgeons reported “systematic abuse, neglect and semi-starvation,” exposure and disease, and that thousands would be “permanently broken down in their constitutions,” if they even survived. Among Richmond’s prisons, Libby, thought to be escape-proof; Castle Thunder, for political prisoners; and Belle Isle, a pestilent open-air enlisted men’s camp upriver on the James, earned reputations for horror exceeded only by Andersonville Prison, in Georgia, whose warden was later tried and hanged for war crimes.

Desperation compelled Libby’s prisoners to dig a tunnel, and, after many setbacks, 109 officers escaped into the cold night of February 9-10, 1864. Two drowned in the James and 48 were recaptured, but succored by free blacks and slaves, 59 eluded their pursuers and reached federal lines. Afterwards, Major Turner determined that one of his African American prisoners, Robert Ford, a federal teamster from Frederick, MD, had likely measured the tunnel length required so escapees could surface behind a fence. Two white women held at Castle Thunder who were either Union spies or sympathizers also helped plan and enact the scheme, but it was Ford who received the 500 lashes that nearly killed and left him “helpless” for six weeks. In later testimony, Ford was said to endure the unprecedented whipping “without ever betraying certain other persons who had aided in concealing said prisoners after their escape.” Ford never fully recovered, yet escaped alone in July 1864, making his own way to Washington, D.C.

For his heroic actions, Congress passed a bill in 1868 awarding Robert Ford $814 (the same amount he would have earned during incarceration), acknowledging him “very serviceable to the Union prisoners, affording them information, and aiding their escape.” He secured employment as a laborer for the Treasury Department, but died in April 1869, partly due to his flogging by Major Turner. A Congressman writing in tribute to Ford said, “the nation owes him a debt of gratitude.”

At top right, the Mitchell Collection’s rare CDV of Libby guarded by federal troops after the fall of Richmond. Note the whitewashing Confederates applied to many lower story prison walls after the 1864 escape, both to identify their prisons and deter escapees from hiding in shadow.

At the time this CDV was distributed, Libby confined CSA leaders upstairs, including Vice Pres. Alexander Stephens, Secretary of War James Seddon, and Secretary of State Robert Hunter. Into its feared, rat-infested cellar dungeon went warden Turner, who facing charges of cruelty and robbery was later exonerated for lack of evidence. On April 5, 1865, President Lincoln bravely toured the still-smoking city on foot. When he came to Libby Prison, his mostly black crowd of followers cried out “We will pull it down!” to which Lincoln replied, “No, leave it as a monument.”

However, Libby became much more. With Victorian exuberism, in 1889, as the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ historic voyage approached, a group of Chicago businessmen created the Libby Prison War Museum, relocating the structure 600 miles by rail to the site of Chicago’s huge, World’s Columbian Exposition. Libby was carefully dismantled and loaded into 132 box cars. Rebuilt and operational within three months of the Exposition’s opening, more than 100,000 had already toured the Civil War museum to rave reviews. Attendance swelled during the 1893 Exposition that drew 27 million from all over the world.

The venue advertised it would include “African Slavery in America” and exhibit thousands of war relics and memorabilia. It proudly featured the very Bible that Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson used to teach “his famous Colored Sunday School.” Museum guides, who organizers claimed were all ex-POWs, described how the war’s greatest prison break was abetted by female spies, but omitted telling about Robert Ford and the role played by Virginia’s black populace.