Fact or Fable? The Enduring Legend of Forty Acres and a Mule.

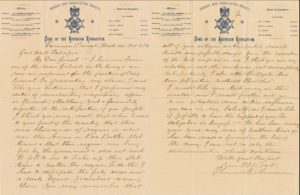

This fascinating 2-page letter by Col. Thomas M. Anderson, U.S. Army (a nephew of Ft. Sumter’s famous commander, military historian, and founding president of a Sons of the American Revolution chapter), is addressed to former Confederate General William B. Taliaferro, a Harvard educated lawyer, prominent judge, and recent member of the Virginia House of Delegates. (Taliaferro was the brilliant field commander who not only repulsed black troops of the 54th Mass. in their heroic but costly attacks on Battery Wagner at Morris Isl., SC, in July 1863, but again at the tragic Battle of Olustee, FL, in February 1864.)

Following the Civil War, Col. Anderson was appointed the Army’s Commissioner of Registration for Virginia’s Lower and Middle Peninsulas, administering the Oath of Loyalty to Rebel planters, officers, and politicians – a federal requirement in order to have land returned and qualify for positions of public trust. Some 28 years later in 1894, Anderson has become a candidate for the rank of general. He writes requesting Taliaferro’s deposition as a witness to his service among Virginia’s tidewater aristocracy during Reconstruction. In part, he patronizingly asks: “In presenting my claims, I would like your testimony that I performed my duties of reconstructing & registering officer in Gloucester, Matthews, York, and James City counties to the satisfaction of your people … that there were thousands of negroes in what were then known as [Union Major General] Ben Butler’s Slab towns … being fed by the government … [and it] fell to me to brake up their Slab-towns & scatter the negroes. To do this I had to dissipate the forty acres and a mule legend prevalent among them …”

“Slabtown” was the nickname for any of the three ramshackle settlements escaped slaves had erected amid the ruins of Hampton and Yorktown, VA. It so appears that Anderson’s responsibilities included clearing out the nation’s first self-contained African American communities for landowners he pardoned who wanted their black settlers dispersed. By an extraordinary coincidence, Anderson writes the very officer who commanded all Confederate forces in South Carolina at the end of the war, including the period when Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman invaded the state. Accordingly, Taliaferro would have known it was not merely “legend” that in mid-January 1865 Sherman issued Special Field Orders No. 15 (in six parts), settling 40,000 freed slaves on land abandoned or expropriated from coastal landowners in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida – all places where Taliaferro had held district commands.

With masses of freed slaves drawn to their liberating Army, Sherman and Secretary of War Stanton met with twenty black pastors in Savannah, GA, on January 12, 1865 to find a way to support them. Questioned for the first time what the freedmen wanted and where they belonged, Rev. Garrison Frazier replied “we want to be placed upon land … till it by our own labor … and to live by ourselves, for there is prejudice against us in the South.” Endorsed by Lincoln, Sherman’s “Orders” formed the basis of the claim that the federal government promised 40 acres and a mule – an ex-Army mule that Sherman suggested to the pastors but never mentioned in his Orders of January 16th.

With the idea that freedmen could eventually purchase or lease their parcels from the government at low rates, indeed, by June 1865 around 10,000 heads of households were settled on 400,000 acres on coastal islands and up to 30 miles inland. Incoming President Johnson, however, refused to honor the accord and returned all land to its former owners. His decree was first delivered to the freedmen of Edisto Island, SC, later that year in a heart rending, tear-filled apology by General Oliver O. Howard, Head of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Thus far, thanks to the new President and men like the dutiful Colonel Anderson, Sherman’s promise became a myth and Reconstruction had come to resemble “Restoration.”