“Amos ‘n’ Andy,” the Enduring Radio Show Had Americans Laughing at Racial Stereotypes.

Radio broadcasting was still in its infancy when the “Amos ‘n’ Andy” show appeared in 1928, featuring humorous 15-minute sketches based on crude racial caricatures that resurrected the black minstrelsy of a bygone era. Quickly becoming one of radio’s most popular series, its white creators and central characters, Freeman Gosden (Amos) and Charles Correll (Andy), based their vignettes on poor farm hands who had come North during the Great Migration, and their fumbling, often unscrupulous attempts to gain acceptance. Mimicking southern dialect, the duo applied “blackface” solely for advertising, public appearances, and for the RKO Radio Pictures feature-length film released in October 1930.

The typical plot had Amos, a philosophical cabbie, narrating George “Kingfish” Stevens’ madcap attempts to swindle a gullible Andy, “the big dummy,” who could often be persuaded to invest in the Kingfish’s half-baked schemes. Considered great entertainment at the time, African Americans were split on its racial and ethnic portrayals. While the usually outspoken Chicago Defender hosted a reception, picnic, and parade for the show’s cast, which now included a few black actors, the Pittsburgh Courier excoriated and sought its banishment from the airwaves. After WW II, it was the advertisers who cancelled, deciding the blackfaced burlesque was a poor reflection on both the black community and themselves. The radio show was finally cancelled in 1960.

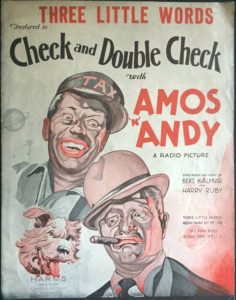

Above, is the 1930 sheet music published for the only “Amos ‘n’ Andy” movie ever produced. Although a success, the Great Depression only worsened, and the novelty of seeing the famous radio stars in blackface wore thin. Moreover, despite the stars top-billing, they played only minor roles whose mishaps and buffoonery were tangential to the storyline. Of greater consequence, Duke Ellington and his “Cotton Club Band” not only provided the music, but were highlighted onscreen, propelling Ellington into the national spotlight. The band was racially integrated with light-skinned Puerto Rican trombonist Juan Tizol, and a Creole clarinetist, Barney Bigard. The film’s director insisted that they, too, apply makeup to appear as dark-skinned as Amos and Andy.

With the advent of TV, a sequel appeared in 1951 with a larger cast of all-black actors set in Harlem. Although the bumkins’ roles and dialect remained, they were purposely contrasted with urbane black professionals who had entered New York society, albeit a segregated one. Despite the Pittsburgh Courier’s approval, the NAACP lashed out, saying, “Every character is either a clown or a crook,” and the series was cancelled in 1953. The show’s popularity ensured its reruns remain in syndication until 1966 when the Civil Rights Movement had Americans reconsidering their core values.