The Internal Slave Trade – “Sold Downriver,” shipping healthy slaves from Richmond to New Orleans.

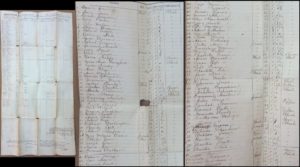

At far left, a well-worn, Slave Cargo Manifest from Richmond, March 20, 1851. The huge, one-page document (16 ½” x 31 ½”), lists a total of 89 slaves by name, sex, age, stature, complexion, shipper, and owner. Sections enlarged at center and right.

This extraordinary “coastal slave trade” piece reads at top, “MANIFEST OF SLAVES intended to be transported on board the Barque Virginian of Richmond Virginia wherof Nathaniel Boushis Master, of the burthen Three Hundred & Nine tons, and bound from the Port of Richmond, State of Virginia, for the Port of New Orleans, in the State of Louisiana, this Twentieth day of March 1851.” Captain Boushis signs his name attesting that no slave had been imported from Africa after January 1, 1808, the date the Transatlantic Slave Trade ban to the U.S. became law.

The document reflects the high point of the “Internal (or Domestic) Slave Trade,” a trade between regions of the upper and lower South. Duplicate “inward manifests” were required to be filed both in advance and upon arrival at New Orleans by Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution. It is worth noting that so many slaves were shipped directly from Richmond to New Orleans that the manifest form is pre-printed with the names of both ports.

By 1830, Richmond had supplanted Charleston as the epicenter of America’s slave trade. Processing over 80,000 slaves per year at its apogee, it was the Commonwealth’s largest industry and second only to New Orleans in sales. The city’s Shockoe Bottom slave market comprised thirty square blocks with several dozen dealers, numerous slave pens, auction houses, and jails where owners and traders could board or punish slaves for a fee. Though a latecomer to rail service, the inland port had riverfront dockage with extensive canals, state roads and turnpikes – all built with slave labor. Today, it is estimated that over 40 percent of African Americans have an ancestor traded from Richmond.

At right, are enlargements showing the names of slaves to be shipped South. Note that a number of them have famous Virginian surnames, including Bland, Carter, Lee, Mason, Taliaferro (pron. Tolliver), and Washington. One slave, Adam Holliday (Holiday), is listed as sick and stayed behind as certified at the left image’s lower right, by 1st Lieut. John G. Rushwood of the U.S. Revenue Cutter Duane, a two-masted sloop on tax and customs duty, a service that later became the Coast Guard.

The column at right lists some of the more notorious southern slave dealers, with braces signifying their separate groups of slaves. Among those awaiting their human cargo at New Orleans, were John Hagan, a prominent slave dealer who had slave pens in both Charleston, SC, and New Orleans, and William F. Talbott, a Lexington, KY slave trader. He frequently advertised to Tennesseans offering to buy their slaves for the New Orleans Market. One Talbott ad read: “I will pay $1,200.00 to $1,250.00 for number one men and $850.00 to $1,000.00 for young women. In fact, I will pay more for likely Negroes than any other dealer in Kentucky.”

Another notorious dealer listed on the manifest is Thomas G. James of Natchez, who placed the following advertisement in a Concordia, Mississippi, newspaper:

“NEGROES—The undersigned would respectfully state to the public, that he has leased the stand in the Forks of the road near Natchez, for a term of years. And that he intends to keep a large lot of negroes on hand during the year. He will sell as low, or lower than any other trader at this place or in New Orleans, who has the same description of negroes. He will endeavor to give satisfaction to every person who will favor him with their custom. He is hourly expecting an additional lot to arrive, and will receive by sea and Railroad from Virginia, during the year, a constant supply of various kinds of servants. He has a first-rate blacksmith, a wagon, a carryall, and three fine mules. Call and see. THOMAS G. JAMES. Natchez.”

These, and several others listed on the manifest were constant buyers of “prime” Virginia slaves, those usually between the ages of 16 and 24 that fetched the highest prices. And every dealer was on the lookout for “fancy girls” to satisfy the salacious whims of “southern gentlemen.”

In November 1841, on just such a voyage to New Orleans, the brig Creole left Richmond with 103 slaves and picked up another 32 at Hampton Roads. At-sea, Madison Washington led eighteen of his fellows to overpower the crew, killing the captain. Fleeing to the Bahamas, the British eventually freed 128 of the captives thus becoming North America’s most successful slave revolt.

From 1819 to 1861, nearly a quarter-million African Americans were herded aboard steamers and sailing ships heading down both the Atlantic seaboard and Mississippi River to southern ports where avaricious slave dealers expected shipments once or twice a week. Bondspersons often shared shipboard space with livestock, but what they dreaded most were the coming unspeakable cruelties, a shortened lifespan from disease and toiling under the tropical Sun. And, that even when traveling together, their families would be broken apart at any time and for any reason.

If ever there had been a chance of escape it would be impossible now.