Sam Langford, the “Boston Bonecrusher” (1886-1956), Pound-for-Pound, the World’s Greatest Uncrowned Boxer.

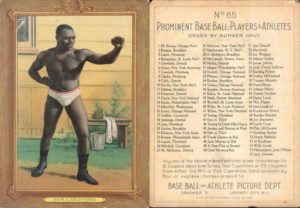

Above, a rare Turkey Red Cigarettes 6 x 8-inch T9 series cabinet card No. 65, circa 1910. At right, offered alongside the T3 baseball series, the reverse featured 26 other champions of the day. Considered the most desirable of all boxing issues, the limited-time premium rewarded smokers who purchased enough product.

Forgotten in time, Sam Lankford’s saga is recounted by Clay Moyle in Sam Langford: Boxing’s Greatest Uncrowned Champion (2008). Born in Weymouth, Nova Scotia, Langford was a descendant of slaves who had fled there with Loyalists during the American Revolution. Little is known of his upbringing except for running away at age 12 to escape an abusive father. Making his way to Boston, he swabbed floors at an athletic club and was soon sparring with the boxers who trained there.

By age 15, Langford was an amateur state champion and matured to take on the worlds greatest. Realizing there was more money to be made fighting in the heavier classes, the small, lightweight turned pro and gained enough to contend in every weight category, including heavyweight. Even though he rarely exceeded 165 pounds and his opponents were lankier, it wasn’t long before the prospect of facing the five-foot-seven-inch dynamo became any boxer’s worst nightmare.

Leading sportswriters, like Nat Fleischer were effusive, saying “He possessed strength, agility, cleverness, hitting power, a good thinking cap and an abundance of courage. He feared no one. But he had the fatal gift of being too good, and that is why he often had to give away weight in early days and make agreements with opponents. Many of those who agreed to fight him, especially of his own race, wanted an assurance that he would be merciful or insisted on a bout of not more than 6 rounds,” in an era when 50 or even 100 rounds occurred.

When the 20-year-old took on 28-year-old Jack Johnson, in 1906, he gave up 29 pounds to the heavyweight to last 15 rounds before losing, saying it was, “the only real beating I ever took.” Johnson refused to fight him again, stating several years later, “I don’t want to fight that little smoke. He’s got a chance to win against anyone in the world. I’m the first black champion and I’m going to be the last.” Besides, he added, “Nobody will pay to see two black men fight for the title.”

During his 25-year career, Langford endured the “color line” as the “Boston Tar Baby,” rarely getting a shot at championship titles. In 1904, he fought World Welterweight Champ Joe Walcott to a draw in a 15-round contest that most felt Langford deserved, including The New York Illustrated News. A too-high percentage of his fights resulted in draws. In 1910, he defeated Stanley Ketchel by decision in a hard-fought, 6-round non-championship Middleweight bout. Later that year, Ketchel was murdered before their 45-round title event could be held. But overseas, Langford won titles in England, France, and Australia.

Whereas the racist wisdom of the era postulated black fighters as having a harder skull, being insensible to pain with stomachs invulnerable to punches, as well as having a propensity towards violence, the reality was altogether different. At best a boxer’s career might span a couple of decades, and regardless of injuries from those who towered over him, none could say that Sam Langford’s skill had failed or his indomitable spirit was ever broken.

Iconic heavyweight champ, Jack Dempsey, recalled in his 1977 autobiography, how as a 21-year-old he refused to fight an aging Langford in 1916, writing, “… I feared no man. There was one man, he was even smaller than I, and I wouldn’t fight [him] because I knew he would flatten me. I was afraid of Sam Langford.”

During a fight the following year, Langford permanently lost sight in one eye, yet continued on for another nine years, the final few with diminishing vision. He battled for the 1923 Mexican heavyweight title despite assistants guiding him into the ring and to his corner between rounds. Langford’s handlers wanted to call the fight off, but needing the money, he refused, and won. He could only see shadows with his “good” eye in 1926, and began losing half his bouts, forcing his retirement.

Under different circumstances he might have won five different weight titles. And though great success had proved elusive, like Jack Johnson, Langford enjoyed the fine clothes and automobiles, displayed jocular demeanor, and like nearly every star of his era, flouted financial responsibility. In 1944, sportswriter Al Laney of the New York Herald Tribune became curious about Langford. Some claimed he’d died, but Laney found him only a few miles away in a tiny Harlem apartment, subsisting on a few dollars each month from a foundation for the blind.

Laney submitted his story, but his follow-ups on Langford’s plight compelled New Yorkers to raise $11,000 to buy him an annuity. In 1952 Langford returned to Boston to spend his remaining years in a private nursing home. Finally, in 1955, but four months before dying, he was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame as the first non–world titleholder accorded the honor. He reportedly said at the time, “Don’t nobody need to feel sorry for old Sam. I had plenty of good times. I been all over the world. I fought maybe 600 fights, and every one was a pleasure!”

Although he had a very high percentage of losses at the end, to put Langford’s career in perspective, consider how he places compared to the combined (and not averaged) professional fight stats of four of the greatest boxers in recent memory. (Langford’s data varies somewhat by source.)

Combined Records of Joe Frazier, Ken Norton, Larry Holmes, and Muhammad Ali:

Fights Won Lost Draw KO’s

223 199 22 2 141

Sam Langford:

Fights Won Lost Draw KO’s

304 214 46 44 138