Sojourner Truth, “The Libyan Sibyl” (c. 1797-1883). Abolitionist, suffragette, activist, and orator.

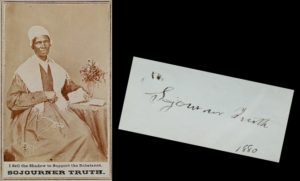

Among several versions, this 1864 Carte-de-Visite, at left, declares “I sell the shadow to support the substance.” Sojourner’s six editions of The Narrative of Sojourner Truth: A Northern Slave (1850), also provided funds for her traveling lectures contending slavery over the course of a 30-year speaking career.

Born Isabella Baumfree, she escaped to freedom with an infant daughter in 1826, and sued in court to recover her son in 1828, becoming the first black woman to win such a case against a white man.

Eighteen years later she heckled Frederick Douglass onstage, yet Douglass recognized her potential enough to encourage and mentor her in like fashion. Though illiterate for most of her life, Truth’s astute extemporaneous rhetoric helped pave the way for upcoming politically-minded abolitionists, like Radical Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, and socially-minded author Harriet Beecher Stowe, whose 1852 novel on the evils of bondage, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was an immediate bestseller even though Stowe had never been south or witnessed plantation horrors firsthand.

In 1862, William Wetmore Story’s classical marble statue, “The Libyan Sibyl,” became a powerful symbol of emancipation. Based on Harriet Beecher Stowe’s article “Sojourner Truth, The Libyan Sibyl,” in the Atlantic Monthly (Vol. XI, April, 1863, also in the Mitchell Collection), the image was said to be in the allusion of Sojourner as eldest of the legendary prophetesses of antiquity who foresees and broods over the fate of her people.

Over time, some 2,000 state and local chapters of abolitionists swung public sentiment away from constitutional issues of slaveholders’ rights and towards the Garrisonian sentiment that slavery was morally wrong. For all that, an epic struggle would be required to separate the enslaved from their masters, and Sojourner was an early advocate for enlisting and equipping black troops. And while most abolitionists ceased their efforts after the Civil War, Truth foresaw great troubles ahead and continued steadfastly along her lecture circuit.

Few are aware that by late-1880, though well-advanced in age, Sojourner Truth had finally learned to read and write. At right, is one of only two or three known Truth signatures; with one, possibly a guided effort and nearly illegible. Under the “Personal” column in Harper’s Weekly of March 11, 1882, on page 3:

“Sojourner Truth writers to us from Battle Creek, Michigan, in reference to recent published paragraphs of her having a fine home, and her having made a will, etc. She says she has made no will, owns no farm, but has a small house encumbered by a mortgage, and has no income but what she derives from the narrative of her life and sale of her photograph, which she hopes, and we hope, her friends will buy to help her along in this one-hundred-and-seventh year of her stay on earth.” Sojourner would pass away the following year.

In 2014, Truth was named in The Smithsonian magazine’s “100 Most Significant Americans of All Time.”