The Scott v. Sanford Case – The Supreme Court Rules “Slaves Have No Rights That Whites Are Bound to Respect.” Democrat’s defend the Court’s pro-slavery rulings in the election of 1860.

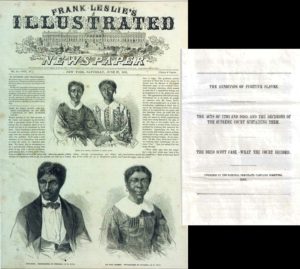

Above, Dred Scott (c. 1799-1858) and his family, drawn from a photograph after the polarizing Supreme Court decision, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, June 27, 1857.

Dred Scott belonged to a Missouri slaveholder who took him into the free state of Illinois and then back again. Scott successfully sued for his freedom because he had resided in a free state, but on March 6, 1857, the U.S. Supreme Court overruled the lower court’s decision.

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney (in office 1836-1864), declared Scott had never ceased being a slave, and therefore, neither he nor his descendants were or could ever be citizens with rights, or sue in court. Even the children of free black parents were deemed chattel. In forming their opinion, the judges contended slaves were “beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race,” whereas the Declaration of Independence proclaimed freedom, dignity, and equality solely among whites – a stance countered by jurist Abraham Lincoln in his masterly “Speech on the Dred Scott Decision,” on June 27, 1857.

The ruling was a huge blow to Abolitionists’ appeals for gradual emancipation, and prompted blacks to clamor for colonizing Liberia and parts of the Caribbean. Worse, the Court’s rendering that Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery had the unintended consequence of invalidating both the Missouri Compromise and Kansas-Nebraska Act, resulting in years of bloody conflict over settlers electing whether to allow slavery within their territories.

For the crucial presidential election of 1860, Democrats nominated Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas to run against Lincoln, a Republican who had achieved national prominence by debating Douglas in 1858. Born in obscurity, Lincoln became a successful attorney and his political star was rising. Appearing before the Supreme Court in 1849, among his rhetorical skills was the rare ability to reduce complex cases into a few simple points, as well – in the absence of today’s opinion polls – to accurately sense the political climate.

Like the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the Dred Scott Decision exposed racially based slavery’s being at odds with the Founders’ “Glorious Cause” of liberty and equality. Increasingly the crux of uncivil and sectional debate, Lincoln believed the Court’s partiality could tear the country apart and that cooler heads must prevail. But compromise was impossible. Speaking to delegates at the Illinois Republican State Convention in 1858, he ominously paraphrased the biblical passage that “a house divided against itself cannot stand.” Emphasizing that the Union be preserved above all else, he warned, “but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.”

At right, The National Democratic Campaign Committee issues a pamphlet for the 1860 presidential election that includes three articles for prospective voters – each centered on slavery: “The Rendition of Fugitive Slaves; The Acts of 1793 and 1850, and the Decisions of The Supreme Court Sustaining Them; and “The Dred Scott Case – What the Court Decided.” At the time, the Democrats were a pro-slavery party and the pamphlet’s arguments were solely intended to reinforce the institution of slavery and slaveholders’ rights.