Orders, Rules & Regulations of U.S.S. BRANDYWINE for the African and Brazilian Stations (1828-1852).

It was primarily slavery, and white slavery in particular, that created the requirement for a strong U.S. Navy. Desiring neutrality, President George Washington found little need for a standing army or navy following the War of Independence and disbanded them both. By 1785, however, the capture, enslavement, and ransom of U.S. merchantmen and their white sailors by Barbary pirates thwarted trade in the Western Mediterranean and its approaches for over 15 years. Diplomacy failed the fledgling Nation. Tripoli’s insatiable demands in exacting tribute compelled President Jefferson in 1801 to create a modern, powerful navy to secure the seaways.

In 1807 Great Britain banned the Atlantic Slave Trade, and the next year deployed increasing numbers of warships off the African Coast to enforce it. The U.S. Constitution of 1787 had banned the importation slaves to the Mississippi Territory and of “persons” within 20 years. Thusly, at President Jefferson’s urging Congress banned the slave trade in 1808, but not until 1819 did it send its cruisers to stanch the flow of African captives to the Western Hemisphere.

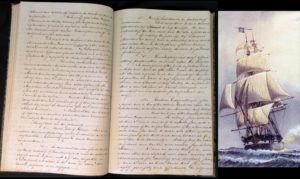

At left, is a remarkable, boldly written 55-page handwritten General Orders ledger for the 54-gun frigate USS Brandywine, at right, launched in 1825 (as an improved version of the famous USS Constitution, “Old Ironsides”). Brandywine, in 1840, briefly patrolled waters off the Coast of Africa and later served in the Brazilian Station’s southern Atlantic region intercepting vessels profiting from slaving. Even so, during the 3-year period Brandywine was deployed from Rio de Janeiro, September 1847 to August 1850, an estimated 180,000 African captives were smuggled into Brazil – the world’s largest importer. Brazil declared its international importation of slaves illegal in 1850, due in part to the U.S. and British naval blockades.

The ledger’s initial eight pages pertain to policy, rules, regulations, and suggested actions toward honest traders as well as with suspected slave runners. To wit: “The United States are sincerely desirous wholly to suppress this iniquitous traffic, and with that view have declared it to be Piracy.” Regarding the Navy’s inexperience: “The Department relies with full confidence on your judgment and discretion so to employ the force under your Command … as indeed, it would be almost impossible to give you specific instructions upon the subject.” It more accurately describes the artifice slavers employed to evade detection and capture: “It is not to be supposed that vessels destined for the Slave Trade will exhibit any of the usual arrangements for their business. They take especial care to put on the appearance … as if engaged in the pursuits of lawful commerce. It is their practice to run into some river or inlet where they have reason to believe the Slaves may be obtained, make their bargain with the Slave factor [broker], deposit their handcuffs and other things calculated to betray them, and then sail on an ostensible trading voyage to some neighboring Port. At the appointed time they return, and all the Slaves are then ready to be shipped, they are taken on board without delay and the vessel proceeds on her voyage. Thus the Slavers do not carry with them any positive proof of their guilt except before they reach the Coast and after they leave it with Slaves on board.” It next cites “a variety of signs and indications of which their true character can at all times be conjectured.” These include, “Double sets of Papers … an unusual number of Water Casks,” and forged certifications, “in lieu of the usual Consular Seal, the [wax] impression is made with an American half Dollar.” The ledger also contains a pencil sketch of the Brandywine hailing a suspected slaver which displays the flag of Argentina to avoid suspicion. A separate bound folder lists the ship’s 480 officers, enlisted seamen, marines, and deserters, their orders, and enlistment expiration dates between 1846 and 1855.

Reviewing the Brandywine’s ledger, however, disturbingly reveals that instead of intently patrolling the Brazilian coastline, the powerful frigate spent inordinate periods in ports of call, entertaining foreign officers and dignitaries, while her captain’s chief concern was quelling the period’s fatal sport of duelling with pistols between his officers.

Overall, despite outclassing its British counterparts in the War of 1812, the Navy Department was so heavily influenced by pro-southern interests that its strength and professionalism were nullified by its squadrons’ underutilized and thinly stretched deployments. Their record compares dismally when intercepting slavers. During the 42 years (1819-1861) that Americans pursued Atlantic slavers, only about 100 vessels were actually seized, versus some 1600 by the British over a contiguous, 52-year period (1808-1860). Inasmuch as the financial rewards for taking slavers as prize-ships was a potent inducement to British commanders and their crews, this motive was never offered to American squadrons.

Stateside however, half the value of a condemned vessel went to whoever informed against it, and American citizens who crewed on slavers were considered to be pirates who could be extradited and hanged. Between 1794 and 1865, the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service, an arm of the Customs Bureau and forerunner of the Coast Guard, captured some 500 slave ships in U.S. waters.

Though their combined effect could have been profound, it is chiefly in hindsight that we adduce such uneven results and failure to cooperate. Even so, the risks and penalties for slaverunning and world-renown of these navies served as powerful deterrents.